When Michael Gove speaks, a storm brews.

When Michael Gove speaks, a storm brews.

The Education Secretary has stated that left-wing myths, denigrating traits such as patriotism, are perpetuated by comedies such as Blackadder, which are used in the classroom to teach history. He continued to remark that “only undergraduate cynics would say the soldiers were foolish to fight”. Gove then attacked the academic integrity of Richard Evans, regius professor of history at Cambridge, who Gove accused of not conducting himself like “a sober academic contributing to a proper historical debate”.

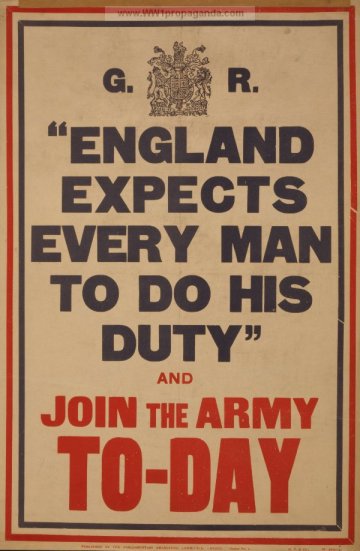

This is not too much of a surprise, and many passive readers will be aware that Michael Gove is keen to promote a new, and quite antiquated, nationalistic history, which has all the trappings of a discredited “Great Man History”. Even yet, the rhetoric that Gove has employed to make his point is extremely aggressive, considering that he states that his opponents act like “undergraduate cynics”. Particularly of interest is Gove insistence that Britain’s participation in World War One equates to a “just war”. The use of that term really is quite shocking and it may be apt to go into this at greater length in another post, as many readers may be interested to discuss this term in the future.

Starting with the rhetoric, it is not an exaggeration to describe Gove’s article in the Daily Mail as an emotionally manipulative diatribe about World War One, This period is still considered “living history”, and a particularly sensitive topic to the nation’s memory and history. In this vein, Michael Gove states that Richard Evans “has attacked the very idea of honouring their [British soldiers’] sacrifice”, while he quotes himself as seeking to “give young people from every community the chance to learn about the heroism, and sacrifice, of our great-grandparents”. This is not carrying a debate with professional conduct – although Gove has not been known for encouraging consensus in his ideas and reforms for education. Using such provocative language to not just discredit his thoughts, but personally singling out Evans again, is extremely unwarranted and constitutes a personal attack on a reputed historian – simply for holding a contrary perspective. Encouraging children to hold a plurality of opinion is certainly an unsafe tradition under such an arbitrary Education Secretary.

“Even to this day there are Left-wind academics all too happy to feed those myths”, Gove determines. It is true that history is often twisted to suit ideology or inclination, and it is the role of the teacher to present an easily digested, accessible, and neutral perspective of how history may be perceived. Present an equal case, give children and students the events, and encourage them to draw their own conclusions. British history is not so fragile that it cannot accept criticism or receive scrutiny for its role in WWI, the events leading to it, and Britain’s leading role in colonialism, imperialism, and expansionism around the world. Rather than deify the war efforts of the nation, we must continue to both commemorate and reflect, and politicians do not have to sing eulogies to the fallen for this sacrifice to be noted. Instead, it should be seen as a symbol of experience and growth that Britain can learn from its history, not wear it.

There are certainly a lot of people who will equate this, as Michael Gove himself states, to an attempt to denigrate values of heroism and courage. While there are certainly a lot of factors behind the beginning of the First World War, and a myriad of reasons why soldiers went to war, there is no attempt in this post to state that British soldiers should not be remembered both as valiant and forsaken. What is important is that we must remember the war from a calmer perspective and with moderation. Any person was capable of heroism or villainy. Generally, they fell between the two.

People fought on the war front, and the home front: many died for a cause they believed in, many died for a cause they did not believe in, and many lived with both memories of pride and sorrow. The point of this article is not to debate the reasons behind the war. Instead, it is to argue that, even though World War One occupies a sacred spot in the shared memory of Britain, we should remember men and women, not heroes and villains. There were valid reasons for war, just as there were valid reasons for not going to war. By transforming WWI into a dichotomy between heroes, who supported war and now stand on pedestals, and villains who were therefore against it – we dehumanise those involved in a tragic war. Why did so many British, Commonwealth, and allied soldiers fall? To defend the liberal western order: apparently, because controlling a quarter of the world via an empire is the epitome of a considerate democracy, despite Germany giving greater suffrage than Britain at the time. Richard Evans has since responded in much the same vein against Gove’s decree that Britain sought to defend this liberal western order.

Let us have a sensitive, and informed, debate about World War One, without the rampant nationalism – all countries involved lost fathers and sons, mothers and daughters. Let us step back from partisan mud-slinging, and rationally consider how and why this dichotomy of opinion has arisen regarding World War One. While memories of WWI live on, and mean so much to us, we should be careful not to rewrite history so belligerently without debate, and to commemorate the past without treading over the graves of those lost. We must remember that other peoples, both past allies and enemies, suffered too – Britain is not alone to shoulder that remorse or regret. We must also continue to conduct British history with maturity; Britain’s role in WWI should never be held to be so sacrosanct that we cannot accept criticism or debate today.

As for Blackadder and other satires, they can be an important tool for encouraging children to take a passionate interest in history. True – they do not occupy the role of “real history”, but there are few who actually consider satirical and dry comedies as historical documentaries. Yes, informative history that assesses sources and debates events is the standard way for teaching history – but teachers acknowledge that they must win students’ hearts before they can encourage their minds. While we may not expect children at the age of fifteen to gain an incisive appreciation for history, we can at least cultivate an interest in history that can persevere into their adult life, when their ability finally matches their curiosity and potential. Until that age, teachers need to keep that spark of interest alive. Rather than berate children about the nationalistic message behind a particular war, as according to new government policy, let us use creative and fun approaches to engage children and adults so they want to learn more. Once children want to learn, the battle is won, and once we accept that Blackadder is not being used to teach “left-wing” morals, and is just a popular comedy that encourages many to form an interest in history, we can actually focus on a more important agenda – how to teach world-class, and world-encompassing, history.

Further reading:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-25612369

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jan/06/blackadder-michael-gove-historians-first-world-war

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/jan/06/richard-evans-michael-gove-history-education

http://theconversation.com/german-historians-have-little-time-for-goves-blackadder-jibes-21826

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jan/30/britain-first-world-war-biggest-error-niall-ferguson